Today, a member of my online parenting group asked a question that many people wonder about, namely when and how to intervene or facilitate or “stay out of” toy taking between children. She cited her understanding of a respectful parenting expert, which seemed to lean in the direction of not intervening and trusting and allowing children to work things out themselves (not exactly how I understand it, but that’s neither here nor there, as that is what this member’s takeaway was.) She somehow felt as if Visible Child tended to recommend the opposite, namely that we should not let children take things from one another.

Today, a member of my online parenting group asked a question that many people wonder about, namely when and how to intervene or facilitate or “stay out of” toy taking between children. She cited her understanding of a respectful parenting expert, which seemed to lean in the direction of not intervening and trusting and allowing children to work things out themselves (not exactly how I understand it, but that’s neither here nor there, as that is what this member’s takeaway was.) She somehow felt as if Visible Child tended to recommend the opposite, namely that we should not let children take things from one another.

Now, to my eyes, neither of those is quite correct, as they introduce a polarized situation in which you must choose between controlling children’s interactions or being uninvolved in their interactions…and anytime we find ourselves in an either/or situation, that’s a good sign that we’re off base. The best answers always lie either in the middle or in the spirit of variation. There is not a “right way” that we must choose. Situations call for all different sorts of responses; our task is to be astute observers and have a flexible repertoire that allows us to respond in a myriad of ways, depending on what is needed in that particular moment by those particular children.

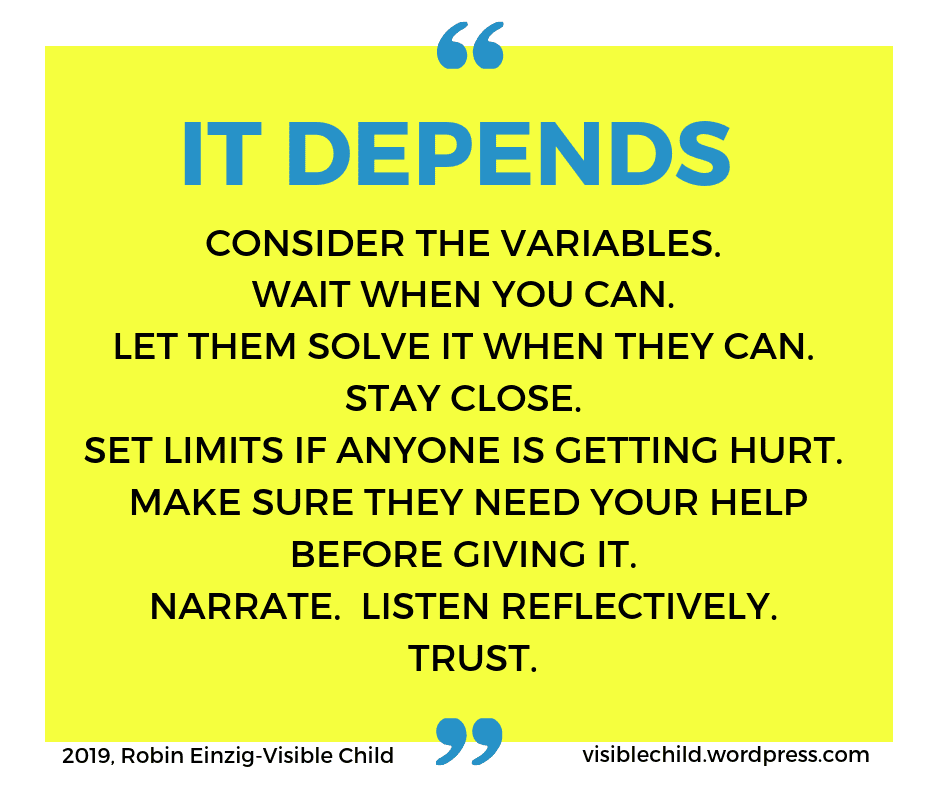

The Visible Child way is always “it depends.” There are times to stay out of it and trust and let children figure it out in an almost entirely hands off way. There are times to actually inject ourselves physically into a situation, for example if a child is being physically hurt. There are times when a simple word or question or look or even just our presence might alter interactions. There are times when we can just narrate and reflect out loud and our words will help children figure things out themselves. There are times when one child is significantly larger or older or more powerful than another and maybe the younger one needs our assistance. There are times when it happens once and there are times when it is constant or chronic, each of which deserve different responses. There are times when our own emotional regulation is strained and we are not able to sit with things and remain calm so we choose to intervene–even if it’s not needed–in order to soothe ourselves and keep ourselves on an even keel so that we can be calm and present with our children. There are times when we are in the park with parents and children we don’t know, and we are sensitive to other parents’ concerns and we have to respond in a way that meets social norms, perhaps differently than we might respond at home. There are times when we know the children and their relationship very well, and we know exactly how much they can handle without our help, which enables us to sit back and trust far more than we might be able to with children we don’t know well. And there are other times, contexts and situations that I haven’t thought of here–this is surely not an exhaustive list.

The thing is, we need to be aware of ALL the possible strategies for ALL of these times, and have them in our pockets so that we can respond in the way that matches the situation and the children that are in front of us right then. I know. It sounds overwhelming. How

can we carry all of that around with us all the time? It is overwhelming when we first begin. For one thing, we have to fight off the “traditional parenting voices” in our heads (and sometimes from helpful relatives!) that say “you shouldn’t let children take toys from one another.” I’m here to tell you: It’s about practice. And intention. If we practice, it becomes automatic and simple and intuitive–it’s something we can commit ourselves to by choice.

All the musing and discussion of this topic reminded me of two powerful examples, one from long ago and one from recently, so I thought I’d share them here in hopes that they will be helpful to you as well.

First, I am reminded me of one of my favorite moments in one of Magda Gerber’s videos (if you haven’t ever watched them, I highly recommend them, they are available from RIE®, and one interview seems to be available online as well). I’m sure I won’t remember it perfectly, so I welcome those who have their hands on the videos to comment and correct the parts I get wrong.

“If they fight, lets say, over an object, that happens all the time, I would allow them to fight, as long as nobody is doing harm to the other. My technique is to move close, to let them know I am here, which already brings about a certain amount of security, and to feel, to give the message, which I personally feel, “I think you can handle it. But if not, I’m here.” And then I use what I always talk about, giving them time to solve the problem. Because the more I trust that they can solve it, the more they do learn to solve it. If every time I jump in and I bring in my version of what’s right, they learn to either depend on me or to defy me.” – Magda Gerber

When we stop to think about it, it’s so true. Life is like that. Our children are going to grow up. They’re not always going to get everything they want. Another child is going to get a prize, or get to be first in line, or get the teacher that they both want, or get to go on a trip or have different possessions. As they get older, they’re going to apply for things that they really want and someone else is going to get them–a college, a job, even a relationship. That’s what life is like. Sometimes things go our way and sometimes they don’t. Emotionally and psychologically healthy people can weather those ups and downs–in early childhood, it’s something we model for them.

Disappointment is a part of life, and the earlier that we learn to treat disappointment as a natural part of life that doesn’t necessarily mean that anything is “bad” or “wrong”, the more competent we will grow to be in a world where things won’t always go our way. We all know adults who can accept failures or rejections or disappointments with grace–they feel their feelings, acknowledge their disappointment without denial of its emotional impact, and they move on…to another task, another school, another team sport, another job. And we all know adults who are felled when they really want something and it falls apart or doesn’t go their way. Where does that come from? Sure, it’s partially personality and individual variation. And it also comes from the emotional resilience they have built over a lifetime, which is certainly influenced by their experience in early childhood and how much disappointment was either seen as something to be avoided (by making sure that things go smoothly and children don’t get too upset) or something to be denied (“get over yourself”, i.e. you don’t have a right to feel how you are feeling.). The thing we most want to model is that it’s okay to feel disappointed and upset–these are perfectly valid feelings–and that it is not an emergency, a crisis, something we have to “fix” right away. We can see the feelings, acknowledge them, and allow them to pass.

The other image that came to mind was from just a couple of weekends ago, when my colleague (and a RIE® Associate), Melissa Coyne, and I did a day long workshop in Los Angeles. In Melissa’s portion of that presentation, she showed a beautiful video of a two toddlers negotiating the possession of a ball in the play yard at the center where she works. In the video, we see two toddlers who are “fighting” over a ball. They take it away from one another repeatedly, sometimes with accompanying screeches, complaints, a small swat, and a couple of brief glances at nearby adults. The remarkable thing about the video is that it goes on for quite a while, and there is no adult commentary or involvement. And the powerful thing about the video is that when parents and caregivers watch it, a great many of them feel as if they absolutely would have intervened, that it was difficult to watch in that sense, hard to “hold back.” Melissa so wisely pointed out the “it depends” factor at work here, namely that the caregiver who was watching and filming them and not intervening knows these two toddlers very well, having been their caregiver since they were small infants…and in turn, the toddlers also know one another very well, having been together in group care since early infancy. That matters–it’s one variable in “it depends.” Would the same interaction happen in that way and be responded to in that way by caring adults if it happened between children who were meeting for the first time in a playground sandbox, or if one of them was much older and larger than the other? Likely not. Once again, context matters…and answers about “how to handle toy taking” change as any number of variables change.

So, what to do, then? (and how to answer that when I’ve just told you that it depends!)

First (as ever): WAIT. PAUSE. This gives you time to make a slow, conscious decision about how you want or need to intervene, rather than making the decision from a reactive, automatic place. In that pause, breathe, and remember your intention to send a message to your children that you see them as competent and capable and trustworthy.

Second: If you’re uncertain what to do (which you probably should be at this point), move in close and sit down. No need to say or do anything or intervene yet. Sometimes just our proximity and presence is enough “borrowed emotional regulation” for children to be able to figure it out. OBSERVE. If you really can’t help yourself and have to say something, try saying “Looks like you both want that”, or if the kids are older, something like “It seems like you guys are having a problem.” And then WAIT. And LISTEN (sharpen up your reflective/active listening skills by reading P.E.T. or How to Talk So Kids Will Listen)

Third: Weigh as many factors as you can manage (again, this will get faster and easier with practice.) A few examples (not exhaustive, by any stretch of the imagination).

- What’s going on?

- Are they upset? One of them? Both of them?

- Whose problem is this? i.e. is it that you are anxious or feeling like you should be doing something, or do the children actually need help?

- Is this happening all day long or is it just this once?

- Can you wait a bit longer?

- Is there an age/size/power imbalance?

- Is it a tough time of day, when they might be hungry or tired and thus have fewer resources?

Fourth: If you decide that this is something they can work out (hopefully!), sit by calmly and just be a presence. Your calm and confident presence will lend them some emotional regulation (they “borrow” ours) and they will figure it out. If you decide that it needs intervention and they are toddlers or young preschoolers, narrate what’s going on. If they are older, say that you can see that they’re having a problem, and ask them what’s going on. Then LISTEN.

Special circumstances:

- If the behavior is frequent, the power or size imbalance is significant, and the younger one is consistently quite distressed, and it’s clear they’re not likely to work it out, then in the moment, consider setting a limit with the one who is consistently taking things. And then attend to the larger picture–is the older one getting one on one time with you? What’s going on with them and the sibling relationship that is leading to them needing to take things so frequently. The behavior is not the problem. The issue is what need they are expressing.

- If it is not about struggle over toys, but is about simply one child frequently coming over and taking the other child’s toys or interrupting their play, take a good look at what’s going on for that child–what are they needing that this behavior is communicating? If the other child is not of an age to speak for themselves or object, they may need you to help facilitate. If they can speak or object and are coming to you with their upset, encourage them to speak for themselves, rather than solving the problem for them. “If you don’t want him to take that, tell him no!” or “You can tell him you don’t like that if you want to.” Steer clear of putting children in roles of “victim” or “aggressor”–that creates an obstacle that prevents things from getting better and damages relationship.

Remember: