Today, I found myself responding to a post on my facebook group about independent play. I wrote a lengthy comment…you know how I am…and then it just seemed that it deserved a blog post, because it’s something that seems to be frequently misunderstood or misrepresented, especially among families that seek to follow the RIE® approach. (I’m super motivated to write by frustration, in case you didn’t know…and nothing frustrates me quite like misunderstanding 🙂 )

Caveat finished. Deep breath.

“I don’t ever play with my kids.” Massive applause and countless “likes.” “Wow, I’m not there yet, but I hope to be some day.” “How did you do that? I must be a failure, because my child won’t do that!”

Ick.

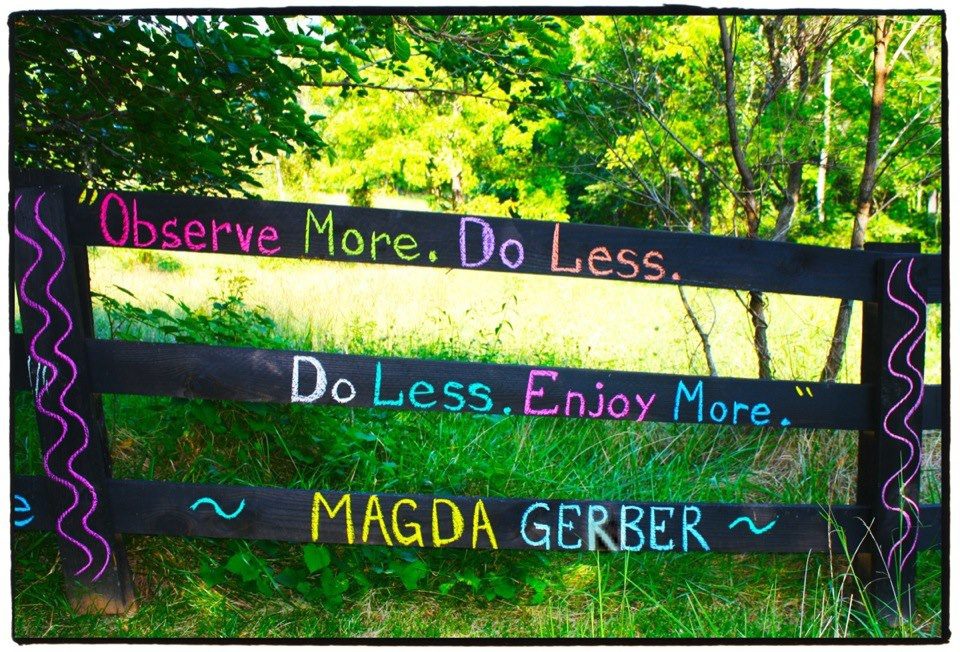

Why ick? Well, maybe ick is the wrong word. It’s just the word that comes to mind when something….well, icky…is being said. As if that clears anything up, eh? I guess the reason I say “ick” is because, well, children are people, and they’re wonderful company and they’re fun to be around. I play with my friends (other adults). I play all the time. I play with people I love. I think play is something that we should heartily embrace throughout our life span, even as it changes form (sometimes). I am a playful person. I love playful people. I’m really uncomfortable around adults who take themselves too seriously. If all of those things are true–which they are, for me–why would I boast about never playing with my child? I love them, I love their company, they love to play, I love to play, play is their language and their world..why wouldn’t we play together sometimes? Why would my child be the exception, the person that I won’t play with, because…um…it’s “bad” for them? That just sounds odd, and well, kinda cold to me. And it sure doesn’t sound or feel like anything I ever learned from Magda Gerber.

(Hint to those of you out there that are thinking this way: Bored is Good. Doing nothing in the summer is Good. This is not your job. You don’t have to do this. It’s better if you don’t do this. And better yet if you never started doing it in the first place. But I’m getting distracted. Kinda. It’s really sort of related, but we’re not here today to talk about what happens in the long run if you insist on entertaining them as babies. Maybe we should. But for the moment, we’re gonna stick to the early years. K?)

So…it’s a question. It comes up again and again. Someone heard someone say that in RIE®, kids are supposed to play independently and parents are just supposed to observe. “Just” and “supposed to” are the key words there, in case you didn’t catch that. Observation is a skill that is absolutely invaluable and its importance cannot be overstated. That’s true. And independent play is a great thing. But there’s the “just” and the “supposed to.” If you’re a concrete thinker or a strict “instructions follower”, they’re gonna hang you up. If there’s anything this parenting gig requires, it’s flexible thinking…and we’re not all made that way. And so you get stuck in rigid phrases like “I’m not supposed to play with my kids” or “They’re supposed to play independently for long periods of time” or “I’m just supposed to observe.”

Yes. And No. (if this hurts your brain, you’re a concrete, black and white thinker. Put “develop flexible thinking” on your list)

So what DOES RIE® say or mean or intend about independent play,, then?

Again (why do the caveats haunt me so?), my word on this is not “the answer” and I do not speak for RIE®. I speak only for myself. So it is me, speaking for myself, when i say that when I read people boasting about long stretches of independent play (which don’t get me wrong, is still a terrific thing), and beaming with pride that they would “never play with their kids!”, my hair stands on end. It’s true. Remember that “ick” up above. Well, yeah. That. Others–some of whom DO speak for RIE® and others who don’t, but follow it–will disagree. That’s okay. Really. It’s okay. Taking information and philosophies in and interpreting and playing around with them and understanding and having our own perspective is really okay. We don’t all have to agree.

Here’s my take on it.

First of all, RIE® doesn’t have rules like that–it’s not a list of what to do, with certain things “accepted” and others forbidden. It’s a list of principles, a way of thinking about and viewing children. The things that people regard as “rules” are simply ways that that thinking about children take form, not a list of requirements or instructions. The “things to do” follow from the way we regard children, not the converse.

In my view,, RIE® is about being responsive to the child, about trusting and allowing and respecting their initiative as they play–from birth. It’s about allowing them the space, time, boredom, and even frustration to find out for themselves what interests them and to develop and learn to rely on their own intrinsic motivation. It’s about having trust and confidence in our children–from the earliest days–as completely and fully competent to be their own “drivers” and make independent decisions, even if they are not on our timetable or doing the things we think they should be doing. It is my firm and robust belief that our children know what they need better than we do.

It is my firm and robust belief that our children know what they need better than we do.

As Emmi Pikler (the source from which RIE comes) emphasized, these approaches are not about independence. They’ve never been about independence–they are about interdependence…the dance…in which children are (more or less) equal partners to us. We trust them. We observe so that we’re not interfering too much. When they invite or request us in, we’re there, in a way that is responsive and present and respectful, rather than “taking over” or instructive or controlling, believing we know better what a child needs than they do. And when the child seems happily engaged again, and don’t seem to need or want our participation, we have no qualms about stepping back and observing once again and see where they go, on their own, when others are not directing or “interfering.”

It is not about independence,” said Anna [Tardos, Emmi Pikler’s daughter], “it is about interdependence, and the adult being present for that child.”

You observe. The more you observe, the better you get at it. The better you get at it, the more intuitive and automatic it will be and the easier the task of parenting will be in the short and the long run.

You trust. You trust your baby or toddler or preschooler or school age child to know themselves best. You trust that they are doing what they need to do. You trust that they are competent and can handle things without you. You trust that frustration is a part of growth, and you recognize that children who are not allowed to experience the natural frustration that they encounter in their own play, or from boredom, will not make the important leaps that are necessary as they mature.

You establish an environment in which independent play can be explored–and even the limits of it pushed a bit, because sometimes that’s a part of learning as well–without any need for you to intervene or correct. You keep the play area safe, and the materials simple and open-ended, so that children can invent and experiment and take risks in the ways that make sense to them.

When they want you to actively play, you do that, to the extent that you are able. You do not have to be “on” for your child all day. You get to have your own boundaries. You remember that play is how children work through, well, everything–their emotions. traumas, stress, relationships, changing knowledge. You join them when you can–sometimes it will be more, sometimes it will be less. You keep an eye on whether they are too dependent on you for play, and you set some limits to encourage them to stretch a bit and re-learn to trust themselves.

You enjoy them. You worry less. You think less about whether you are doing “the right thing” or “the RIE® thing” and more about what feels right to you and what is responsive to the individual sitting or standing in front of you. You play with them. You allow them to play alone. You observe them. You seek balance and reject rigidity.

You enjoy them.

That’s what you do.